The forgotten war heroes who left their own countries to help others – and were never thanked

Robert Gildea, Professor Emeritus of Modern History, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Oxford is a subscribing member of The Conversation. Find out how you can write for The Conversation.

![]() Robert Gildea, University of Oxford

Robert Gildea, University of Oxford

It may come as a surprise that many who fought to save Europe from nazism and fascism in the Spanish civil war and second world war were regarded in their own time as enemy aliens, undesirables, criminals and terrorists – in the words of one of them, Arthur Koestler, “the scum of the earth”.

These were transnational fighters who were involved in rescue and resistance outside their country of origin. The early examples were economic migrants, political exiles or Jewish refugees. Others were displaced when the German and Italian armies shattered the European state system. Later they were joined by escaped political internees, forced labourers and prisoners of war, and by deserters from the Axis armies.

Their stories have been largely forgotten because, after the war, liberated countries constructed myths of national resistance that excluded foreigners. They then fell foul of cold war anti-communism in the west and Stalinist anti-imperialism and anti-zionism in the east. The memory of the Holocaust that became dominant in the 1980s focused on Jewish victims rather than Jewish resisters like themselves.

While researching the French resistance, I came across hundreds of people who were not French but Spanish republicans, Polish Jews, Italian anti-fascists and even German anti-nazis. I concluded that we should talk not about the French resistance but about resistance in France. I also came to think that we should use a much wider European lens to study transnational resistance.

An international research network of 23 historians from 13 countries was brought together to scour the archives in Europe, America and Israel to find traces of these individuals and to piece together their stories. We met in workshops from Belgrade to Dublin over a four-year period, comparing notes, exchanging ideas and hammering out drafts. Here are some of them.

Unearthed stories

Galia Sincari was a Jewish nurse who fled antisemitic Romania to work in hospitals in Spain during the civil war and in the Soviet Union during the second world war. She returned to communist Romania in 1945 but was regarded with suspicion and narrowly escaped a Stalinist purge during the cold war.

Domingo Ungría was a Spanish republican who founded a guerrilla corps in Spain with the help of a Soviet military adviser. He then went to the Soviet Union to organise partisan resistance behind German lines. He died in mysterious circumstances when he returned to head a guerrilla invasion of Franco’s Spain in 1944.

Peter Lake was parachuted into the Dordogne to work with “maquisards” of the resistance in France – who turned out to be not French but Spanish republicans in exile. He was presented to General Charles de Gaulle, who wanted to hear only of French resistance and was told: “You have no business here. Return, return quickly, au revoir.”

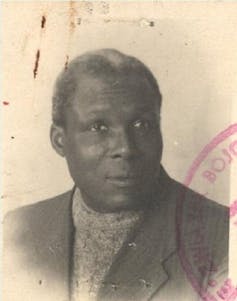

August Agbola O'Brown was a Nigerian jazz player who was a great hit in interwar Danzig and Warsaw. Cut off by the German invasion, he took part in the fateful 1944 Warsaw uprising and hoped to build a “communist heaven” in Poland. Disillusioned, he moved to England in 1956 and died in obscurity.

Left: August Agbola O'Brown. Courtesy of the Association of Polish War Veterans and Former Political Prisoners, Warsaw, Author provided

There were a few more positive stories. Ljubomir Ilić was a Yugoslav architecture student in Paris who joined the International Brigades in Spain. He retreated back to France in 1939 but was then held in a French internment camp, escaping in 1943 to later become a top commander of the resistance. Exceptionally, he had a successful military and diplomatic career in Tito’s Yugoslavia, which opposed both nazism and Stalinism.

Finally, Gerhard Reinhardt, a young German communist, was drafted into a Wehrmacht disciplinary battalion in occupied Greece, then deserted to join the Greek resistance. He did well in communist East Germany, where the official ideology was anti-fascism, and campaigned for what he called “the second round of Greek freedom” after 1967.

Bravery without borders

These ordinary men and women, who were often communists and Jews and were always seen as foreigners, provide a subterranean story of how Europe was saved between 1936 and 1948 from fascism and nazism, antisemitism and nationalism. Stories like this are important now, too, as the European continent faces challenges from nationalism directed against minorities, migrants and exiles. They point the way to a more inclusive, diverse and tolerant Europe.

Take the likes of Syrian refugee Hassan Akkad, the photographer who found work as an NHS cleaner and accused British prime minister Boris Johnson of betrayal for initially denying indefinite leave to remain in the UK to the surviving family of immigrant NHS workers who died fighting COVID before ultimately u-turning. It may be that those who are today denounced as enemy aliens, undesirables, criminals or terrorists, are in fact contributing to making Europe a better place.

Robert Gildea, Professor Emeritus of Modern History, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.