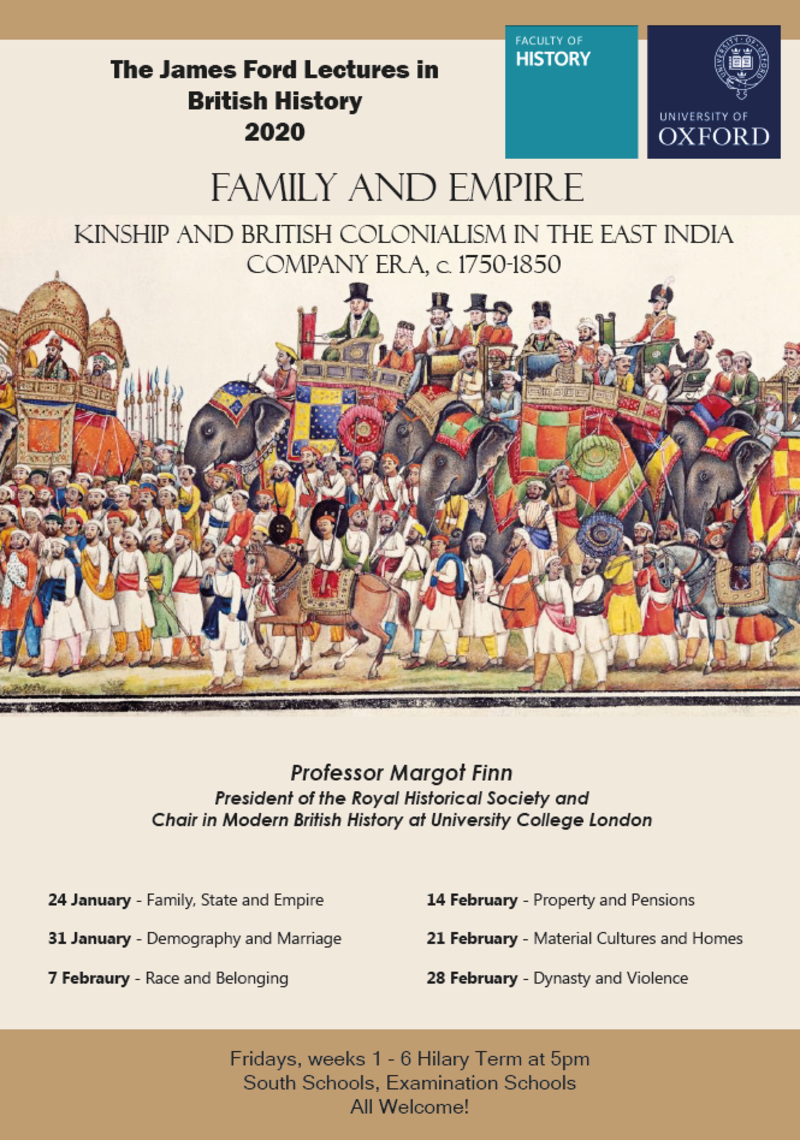

The James Ford Lectures 2020 - Family and Empire: Kinship and British Colonialism in the East India Company Era, c. 1750-1850

Speaker: Professor Margot Finn (President of the Royal Historical Society & Chair in Modern British History at University College London)

These lectures investigate the structures and aspirations of the family as central forces that propelled and maintained the upsurge of British imperialism that marked the century from Robert Clive’s celebrated victory at Plassey in 1757 to the declaration of Crown rule in India in 1858. Historians hotly dispute the causes of British imperial expansion, variously ascribing colonial conquest in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to ideological, cultural, political and economic push factors. By taking family and kinship—in their myriad British and cross-cultural forms—as its focal points, this series of lectures reassesses and resituates these interpretations. It also takes seriously the contribution made to East India Company rule on the subcontinent by the forgotten majority of the British population: woman and children. Without reducing empire to family, the lectures argue that family imperatives made British empire in India both desirable and possible. Contested understandings of kinship, moreover, lay at the heart of British understandings (and misunderstandings) of Indian politics in this period. Family writ large thus emerged as a powerful and contentious paradigm for governance in the Company era. To exemplify these lines of argument, the lectures address topics that include demographic growth, marriage, perceptions of racial difference, property relations, the material cultures of East India Company homes and Georgian and Victorian conceptions of dynastic politics.

Lecture One: Family, State & Empire (24 January 2020)

How would our understanding of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British history differ, if twentieth-century British historians had spent less time reading the first volume of Karl Marx’s Capital (1867) and expended more; effort perusing Friedrich Engels’s 1884 Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State? By following in the footsteps of Engels and de-centring both the patriarchal nuclear family unit and its primary exemplar in modern liberal theory—the acquisitive, autonomous, adult, propertied male—this lecture underlines the foundational role played by ‘baggy’ British families in the making of East India Company rule. It taps into primary sources that include but also extend beyond the official records of East India Company commerce, administration and warfare to access powerful familial impulses that incentivised and rewarded imperial endeavour over successive generations. In the absence of robust British state structures and sizeable cohorts of British personnel in India, reticulated family formations served to underpin trade, administration and war.Viewing family, state and empire from these vantage points raises essential questions about the shape of modernity in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain.

https://ox.cloud.panopto.eu/Panopto/Pages/Embed.aspx?id=ed2f1af8-d994-4f96-822e-ab2100a2d0ea&autoplay=false&offerviewer=false&showtitle=false&showbrand=false&start=0&interactivity=none

Lecture Two: Demography and Marriage (31 January 2020)

Demography is not destiny, but Georgian and Victorian Britain demographic patterns played a key part in fostering imperial endeavour. Too often, British historians restrict their explorations of colonial demography to settler societies, such as the North American colonies, Australia and New Zealand. But British demographic behaviours also had a major impact on why and how the East India Company functioned in South Asia. Demographic surplus—too many aspiring members of the propertied classes, too little domestic capital to satisfy their ever-increasing material needs—propelled men, women and adolescents of both sexes from Britain to the subcontinent. Here, in keeping with both biblical injunctions and the liberal norms of masculine sexual behaviour, they were fruitful and multiplied. The birth of children—including both ‘mixed-race’ progeny and far more legitimate ‘white’ children than historians have hitherto acknowledged—strengthened the familial nature of Company rule and fostered the Company’s implacable territorial expansion. Historians have often underlined the impact of high mortality rates on Company rule in India. This lecture argues that not only such colonial ‘deathscapes’ but also the ‘birthscapes’ of the subcontinent conditioned and drove Company policy. Marriage and childbirth were not merely family matters, but vital motors of British imperialism.

Lecture Three: Race and Belonging (7 February 2020)

Eighteenth-century definitions of ‘race’ focused centrally on family. In Samuel Johnson’s famous Dictionary of the English Language (1755), race was ‘A family ascending’, ‘A family descending’, ‘A generation: a collective family’ and ‘A particular breed’. What impact did both the familial structures and the demographic patterns of the East India Company era have on British understandings and experiences of race? This lecture explores race through lenses that include legitimacy and illegitimacy, place and space, gender and culture. It follows specific men, women and children into (and sometimes out of) ascribed racial identities that entailed distinctive practices of belonging and exclusion. Race loomed large in India, but Company families deployed this concocted category both strategically and selectively to advance their collective aims. In this context, behaviours displayed in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay could diverge both from each other and from the norms of each of their provinces, while the imprint of race in Bengal often departed from dominant practices in the Punjab. Race was a powerful, pervasive and persistent force in Company families in India and Britain precisely because it was labile rather than fixed.

Lecture Four: Property and Pensions (14 February 2020)

Property mattered to Company men and women, as aspiring members of the middling classes and gentry. Prime incentives for Company employment, both capital accumulation and access to desirable Asian luxury goods played central roles in perpetuating the Company’s administrative and military roles long after its original, commercial function as a monopoly had withered. Property relations were also instrumental in melding together the baggy family units that underpinned the Company state on the subcontinent and at home in Britain. Following the money is an essential mechanism for understanding the pattern of British imperialism in India. Sisters, mothers and wives were, moreover, key figures in this colonial calculus: to follow the money, we must cherchez les femmes. The gradual replacement of eighteenth-century private profits with nineteenth-century Company pensions marked an important transition in established British strategies for accumulating and distributing colonial wealth, privileging its orderly transmission to men’s wives and legitimate children. For the defeated or incorporated Indian princely families whose revenues were now also increasingly replaced with Company pensions, the establishment of new British property regimes was also significant, not least in fomenting dissent from British rule.

Lecture Five: Material Cultures and Homes (21 February 2020)

Both Georgian and Victorian understandings of the family were rooted in conceptions of domesticity and home. What types of homes did the Company’s propertied ruling class inhabit on the subcontinent, and how did their South Asian modes of domesticity compare and contrast with their domestic lives in Britain? This lecture explores the ways in which the extended households that contemporaries denominated ‘families’—baggy congeries of blood kin, in-laws, subordinates and hangers-on—functioned to perpetuate Company rule both on the subcontinent and in Britain. Stuffed full of ‘stuff’—artwork, porcelain, textiles, furniture, books, manuscripts and looted war trophies—Company homes were key sites for the making of both domestic and imperial meanings. As built environments that were centres of genteel sociability and parliamentary politics, they functioned to police lines of inclusion and exclusion. Too often accepted as the icon of an English or British ‘island nation’, the country house emerges from scrutiny of the Company family as a conspicuous emblem of imperialism at home.

Lecture Six: Dynasty and Violence (28 February 2020)

Families provided the building blocks of East India Company commerce, administration and warfare on the subcontinent, but family was—though dynastic politics—also a central political prism through which the British viewed the legitimacy (or not) of the successive Indian princely governments they supplanted. What can an understanding of British dynastic thinking tell us about power, politics and governmentality in the Company era—and indeed, in the decades of Crown rule that followed the Company’s demise in 1858? This lecture examines British understandings and misunderstandings of ‘legitimate’ and ‘traditional’ family forms in India and Britain as a window onto wider, cross-cultural developments in nineteenth-century dynastic politics. Concepts and practices of family and kinship both united and divided the British governing classes from the Indian rulers they sought to displace from power. Examining topics such as adoption, sati and royal succession disputes, this lecture suggests the need to locate family and dynasty more securely into our understanding of what it meant to be ‘modern’ in the Victorian era.