A Historian Devoted to Humanitarian Diplomacy

An Early Career Researcher’s Account of one Year with the Global Commission on Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking, 2024-25

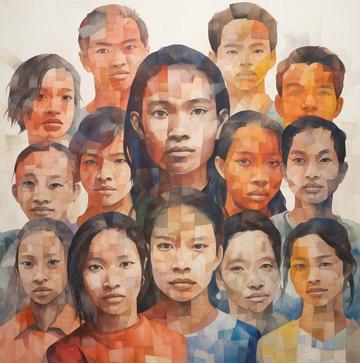

This image is dedicated to supporting the resilience, strength and hope of survivors of modern slavery

“I am a historian devoted to humanitarian diplomacy”. This is how I have been introducing myself over the past year. This new phase of my academic and professional life began in January 2024, when I was encouraged to apply for a Postdoc, centred upon aiding Professor Andrew Thompson with his work for the Global Commission on Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking. Chaired by former British Prime Minister Baroness Theresa May and comprising policymakers, human rights activists, survivors academics, and business people, the Global Commission was set up with the objective of shifting the attention of global policymakers, international business and civil society towards the neglected but pressing issue of modern slavery. As a Commissioner, Prof Thompson has led one of the Commission’s three work streams, which studies responses by the humanitarian community and civil society to modern slavery.

The chief motivation that led me to apply for and accept this post is that I have never exclusively seen myself as an ‘arm chair historian’. The people I came to admire in the course of my dissertation on 20th century French and Italian industrial planning – the French statesman Pierre Mendès-France above all – were hardly ‘ivory tower intellectuals’, but ‘people of action’, engaged not only with providing a nuanced analysis of their surroundings, but also committed to reshape the societies they inhabited.

The three most important strands of work I assisted Prof Thompson with were: engaging regionally-based Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) committed to fighting modern slavery; drafting one of the three chapters of the final report to the United Nations, where the commission indicated its policy recommendations for change; and developing the Framework of Analysis on Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking, the Commission’s tool for prevention.

Prof Thompson and I carried out four regional civil society engagements, or “Deep Dives”, which focused on the West Balkans, West, Central and East Africa, Southeast Asia and Central and South America. These conversations with groups of approximately 12 among human rights activists, trade unionists, lawyers and former law enforcement officials allowed us to identify the types of exploitation that affected a specific region, their key drivers, and the actions undertaken by civil society, governments, International Organisations (IOs) and International Non-Governmental Organisations (INGOs) against these crimes.

Through these exchanges, Prof Thompson and I were able to grasp the dynamism of modern slavery and its adaptability to new political-economic trends. For example, we understood that in critical contexts such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) the criminal networks that exploit forced labour in cobalt and lithium mines are also involved in the trafficking of child soldiers. This discovery made us think about the connection between slavery, armed conflict and the extractive industries involved in the ‘green transition’. In our conversations with Latin American CSOs forced commercial sexual exploitation was identified as a type of “capitalist exploitation”, symbiotically related with the development of unethical tourism. The “Deep Dives” were also major opportunities to collect the CSOs’ recommendations for change, first among which the call for UN Member States and IOs to create the institutional conditions necessary to turn civil society into a major partner in the development of global strategic responses to modern slavery.

We eventually included these insights into the “civil society and crisis contexts” chapter of the Global Commission’s final report to the UN. This exercise did not just constitute an opportunity to closely work with top policy-makers and humanitarian practitioners such as Theresa May and former British Red Cross CEO Mike Adamson, the co-author of our chapter. Contributing to the report was also a chance to apply the knowledge I had gathered on the history of public administration. One of the chief lessons I learnt upon reading the strategic documents of leading IOs and INGOs was that – like the “developmental states” in charge of coordinating Europe’s post-war industrial reconstruction – while characterised by remarkable cooperative ventures, the components of humanitarian system at times undertake siloed and uncoordinated initiatives, which can compromise the effectiveness of their mandates. Mobilising the language of mid-20th century economic planning hence proved useful to call for a reform of the humanitarian system, which would deliver the concerted and coordinated responses necessary to counter modern slavery.

Writing the Framework of Analysis alongside Prof Thompson and my colleague Marly Tiburcio-Carneiro was equally stimulating. This policy-making effort allowed me to closely work with Commissioner Mr Adama Dieng, former UN Undersecretary-General for the Prevention of Genocide, and former registrar of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. The document, submitted to the UN alongside the report in April 2025, identified the general and specific factors that increase collective and individual vulnerabilities to modern slavery and human trafficking, in order to facilitate preventive actions by humanitarian and developmental actors. Once again, the concepts I had mastered during my doctorate proved useful. For example, the notion of “countervailing power” – developed by economist John Kenneth Galbraith to describe organised labour’s ability to challenge monopoly capital in response to ineffective government regulation – helped illustrating the framework’s quest to empower civil society’s ability to confront exploiters and traffickers in the face of state failure.

Overall, the most important lesson I drew from this experience is that history is no siloed discipline. Historians are versatile carriers of nuanced research methods, which can allow policy-makers to better understand and effectively tackle the global challenges of our time. As the French historian Marc Bloch taught us, the “historian’s craft” is too insightful for them to retreat into the comfort of an imaginary antiquity store, sealed off from the present world and its problems. After having spent one year with Prof Thompson, I can proudly say that Bloch’s lesson has not gone unheard.

I am indebted to Prof Lucie Cluver of the Department of Social Policy and Intervention; to Prof Murray Hunt of the Modern Slavery and Human Rights Policy Evidence Centre; and to the Global Commission for having funded my research.

Dr. Cesare Vagge has worked as a Postdoctoral Research Assistant to Prof Andrew Thompson since April 2024. He is currently a staff member at the Department of Social Policy and Intervention, and an Associate Member of both the Faculty of History and Nuffield College. Dr. Vagge completed his DPhil in Modern European History at Merton College, Oxford in May 2024 under the supervision of Prof Martin Conway