Why was British India Partitioned in 1947? Considering the role of Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Key words: Empire, Government, Ideas, Role of individuals in encouraging change, India, Pakistan, South Asia, independence, decolonisation, nationalism

‘The Long Partition’

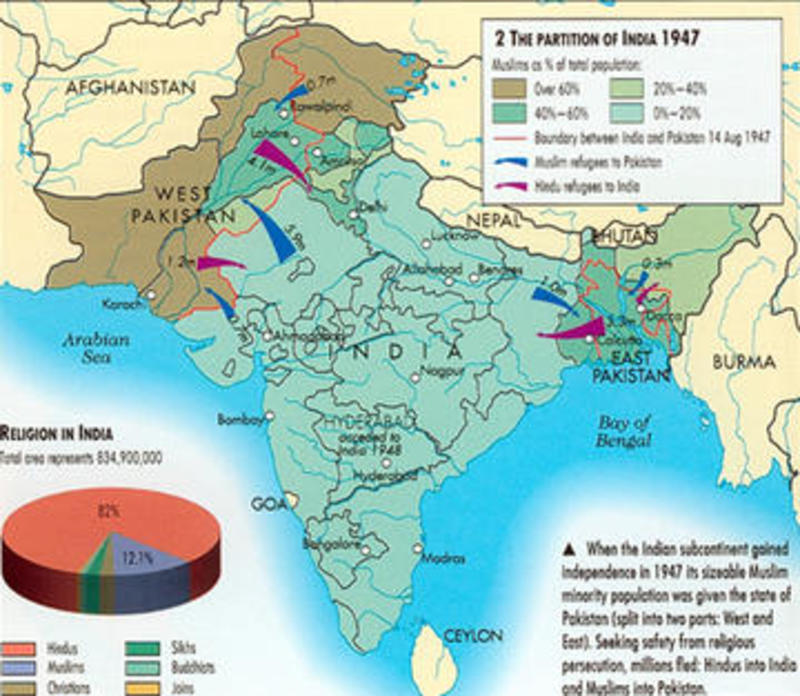

In August 1947 British India was partitioned, ending three hundred years of colonial rule with the creation two independent nations: India and Pakistan (comprising West and East Pakistan, present-day Bangladesh). From the tumultuous and tragic set of events that encompass this ‘Great’ and ‘Long’ Partition, much is set in stone: partition caused the ‘greatest mass movement of humanity in history’.

Twelve million refugees moved across new national borders drawn up by the British barrister Sir Cyril Radcliffe (who had famously never travelled further east than Paris before being tasked with drawing up the lines of partition). Crudely, this was a division based upon religious affiliation, with the creation of a Muslim majority in West and East Pakistan and a Hindu majority in India. Between 500,000 and 2 million souls perished as a result of the ensuing upheaval and violence. 80,000 women were abducted. India and Pakistan have since fought three wars over disputed boundaries in Kashmir (1947, 1965, and 1999).

In the long term, Partition has meant an ‘enduring rivalry’ between two nuclear-armed nations and continues to define the tone and character of Indian and Pakistani politics to this day. This resource takes just one approach to investigating Partition by analysing the role of a key individual at the heart of the high politics of Partition.

Historiography: At A Glance

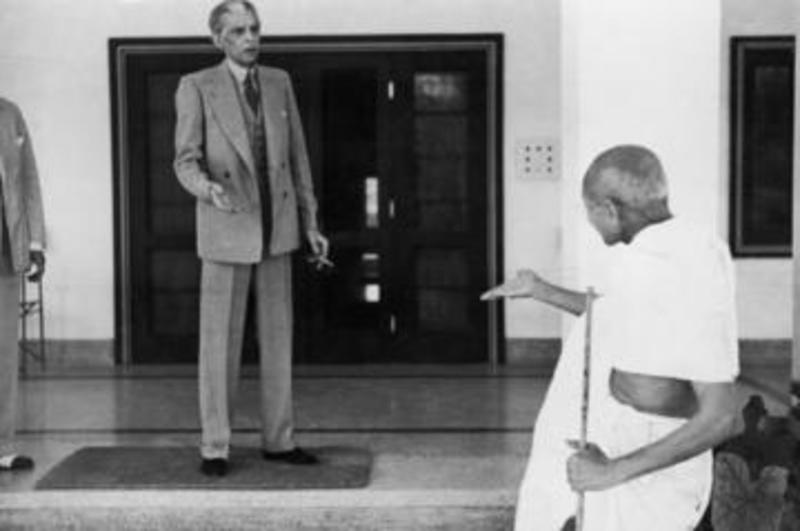

Most scholars today emphasise that Partition was neither an inescapable consequence of irreconcilable differences between Muslim and Hindu populations, nor an inevitable political manoeuvre by the British following decades of ‘divide and rule’. Rather, a complex interplay of factors, including rising communal tensions in the 1930s, political choices made by elites at both national and provincial levels, the impact of the Second World War and the widespread breakdown of law and order following the ‘Great Calcutta Killing’ in 1946 are important to consider as factors. As a caveat, much work that dwells upon the role of individuals as key stimuli to change is rather dated (or has at least been greatly revised and added to in recent decades). Caricatures do however still loom large in the literature, with accounts that present Nehru as a handsome, warm personality close to the “Hollywood version of a British prince”, the Last Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten standing in opposition to that of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who is often defined as a cold, calculating presence. That the Congress Party politician Sarojini Naidu joked she needed a fur coat when in his presence is testament to this enduring characterisation. Nehru thought that Jinnah represented “an obvious example of the utter lack of the civilised mind,” whilst Gandhi called him a “maniac” and “an evil genius.”

The Role of Muhammad Ali Jinnah

This resource invites us to consider how a secular, whisky-drinking, clean-shaven dandy with a penchant for Savile Row suits who rarely prayed at the mosque became seen as the ultimate champion of Muslim minority rights in India and who is today revered in Pakistan as the Quaid-i-Azam [Great Leader], whilst being widely reviled to this day by Indian nationalists as a harbinger of division and violence. He has been seen as the symbolic figure behind the two nation theory: an ideology that stressed religion, rather than language or ethnicity as the primary unifying characteristic to define populations in British India, meaning the necessity for the creation of two distinct nations at the end of empire. Ultimately however, Jinnah is perhaps Partition’s most contested and misunderstood character.

Born in 1876, Jinnah was educated at the Christian Missionary Society High School in Karachi before being sent to London in 1893 by his father to join Graham's Shipping Company before he entered Lincoln's Inn to study law (becoming the youngest Indian at that time to pass the bar in the process). In London, Jinnah discovered nationalist politics, assisting Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian Member of Parliament before returning to practise law in Bombay (at that time the only Muslim barrister in the city) which earned him considerable wealth and status. He joined the (mainly Hindu) Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, urging cooperation between the two organisations, describing the potential threat of Hindu domination of India as “a bogey, put before you by your enemies to frighten you... from cooperation and unity, which are essential for the establishment of self-government.” In 1916, Jinnah succeeded in urging the two organisations to present the British a common set of demands called the Lucknow Pact.

Gandhi's emergence as a key political figure in the 1920s meant the marginalisation of Jinnah within Indian politics. Deeply resenting the ways Gandhi brought a spiritual sensibility to the political mainstream, Jinnah was booed off stage at a Congress Party meeting in December 1920 when insisting on calling his rival ‘Mr. Gandhi’, rather than referring to his spiritual title, Mahatma [Great Soul]. A mutual dislike continued to grow: by the 1940s their relationship had grown so poisonous that they could barely be persuaded to sit in the same room. By this time, Jinnah had become the leading figure in a Muslim League that was advocating a separate homeland for the Muslim minority in India, a position he’d opposed earlier in his career, claiming that the option of Partition was simply “a bargaining chip.”

"India divided or India destroyed"

In his address, Jinnah emphasises that the Muslim League was the sole organization committed to voicing the concerns of Muslims in India, arguing that they’d been betrayed after the 1937 elections with Muslim interests inadequately catered for. A divorce from Congress was advocated, with fears that the Constituent Assembly, much like independent India’s political life would be dominated by Hindus. Furthermore, since Muslims would have a key part to play in the political life of an independent India, they too must also have a role in decisions made with regard to independence, whilst also stressing that Hindus and Muslims constituted different nationalities: this is the two-nation theory.

With Gandhi and Nehru spearheading the ‘Quit India Movement’ during the chaos of the Second World War, both ending up in prison, Jinnah was able to define himself as a key British ally amidst the chaos, earning sympathies and consolidating opinion behind him as the best protector of Muslim interests against a Hindu dominance. In 1945-6 the Muslim League succeeded in general elections, widely becoming recognised as a ‘third political force’ in India alongside Congress and the British. With tensions increasingly heightened over the 1940s by regional political leaders, such as H. S. Suhrawardy, Muslim League Chief in Bengal, who provoked rioting against the Hindu populace in Calcutta, civil disturbances continued to rise. With the British administration feeling increasingly unable to manage what seemed an steadily worsening political situation, the then British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, announced before Parliament that British rule would end in India “a date not later than June, 1948.” This was ultimately brought forward by a year by the British administration.

Partition was even by the late 1940s just one in a number of potential political outcomes. The notion of dividing the Indian subcontinent into Hindu-majority and Muslim-majority areas as is now characterised as the brainchild of Jinnah’s Muslim League went through various stages of evolution. Jinnah was most in favour of federation, given that Muslims were scattered right across the country. Nehru proved steadfast however in advocating a centralised and unified Indian state.

In the end, Nehru got a centralised Indian state, but not a unified one. Jinnah is often cast as the victor in Partition, achieving his goal of an independent Pakistan, yet he complained bitterly before his death in 1948 that the final settlement was "moth-eaten" and incomplete.

Questions for classroom discussion

- How far was Muhammad Ali Jinnah responsible for the Partition British India in 1947?

- What was the most important reason for the Partition of British India in 1947?

- How far was the Lahore Resolution of 1940 a defining moment in Jinnah’s transition from advocate of unity to advocate of partition ?

- How important is the context of Jinnah’s speech (date, location, audience) at the Muslim League in 1940 in determining it’s content and tone (as well as the passing of the Lahore Resolution)?

- Why is Muhammad Ali Jinnah such a maligned figure in the eyes of Indian nationalists?

Teacher guidance

This resource reflects a historiographical debate regarding the end of the British Empire in India and its subsequent partition. It invites students to consider the extent to which key individuals were primarily responsible for the Partition. Using Muhammad Ali Jinnah as a case study, it invites students to dive deep into Jinnah’s past to explore broader changes in Indian society from the early twentieth century as experienced by Jinnah and the development in his own thinking as a result, whilst considering the key factors overall that led to Partition in 1947.

Supplementary materials

[1] Selection of Passages from the Presidential address by Muhammad Ali Jinnah to the Muslim League (Lahore, 1940)

“It is extremely difficult to appreciate why our Hindu friends fail to understand the real nature of Islam and Hinduism. They are not religions in the strict sense of the word, but are, in fact, different and distinct social orders; and it is a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality; and this misconception of one Indian nation has gone far beyond the limits and is the cause of more of our troubles and will lead India to destruction if we fail to revise our notions in time. The Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, and literature[s]. They neither intermarry nor interdine together, and indeed they belong to two different civilisations which are based mainly on conflicting ideas and conceptions. Their perspectives on life, and of life, are different. It is quite clear that Hindus and Mussalmans derive their inspiration from different sources of history. They have different epics, their heroes are different, and different episode[s].”

“The present artificial unity of India dates back only to the British conquest and is maintained by the British bayonet, but the termination of the British regime, which is implicit in the recent declaration of His Majesty's Government, will be the herald of the entire break-up, with worse disaster than has ever taken place during the last one thousand years under the Muslims. Surely that is not the legacy which Britain would bequeath to India after one hundred fifty years of her rule, nor would Hindu and Muslim India risk such a sure catastrophe.”

“Muslim India cannot accept any constitution which must necessarily result in a Hindu majority government. Hindus and Muslims brought together under a democratic system forced upon the minorities can only mean Hindu Raj. Democracy of the kind with which the Congress High Command is enamoured would mean the complete destruction of what is most precious in Islam. We have had ample experience of the working of the provincial constitutions during the last two and a half years, and any repetItion of such a government must lead to civil war and [the] raising of private armies, as recommended by Mr. Gandhi to [the] Hindus of Sukkur when he said that they must defend themselves violently or non-violently, blow for blow, and if they could not they must emigrate.”

“Mussalmans [muslims] are not a minority as it is commonly known and understood. One has only got to look round. Even today, according to the British map of India, out of eleven provinces, four provinces where the Muslims dominate more or less, are functioning notwithstanding the decision of the Hindu Congress High Command to non-cooperate and prepare for civil disobedience. Mussalmans are a nation according to any defmition of a nation, and they must have their homelands, their territory, and their state. We wish to live in peace and harmony with our neighbours as a free and independent people. We wish our people to develop to the fullest our spiritual, cultural, economic, social, and political life, in a way that we think best and in consonance with our own ideals and according to the genius of our people. Honesty demands [that we find], and [the] vital interest[s] of millions of our people impose a sacred duty upon us to find, an honourable and peaceful solution, which would be just and fair to all. But at the same time we cannot be moved or diverted from our purpose and objective by threats or intimidations. We must be prepared to face all difficulties and consequences, make all the sacrifices that may be required of us, to achieve the goal we have set in front of us.”

For full text: Access online via Columbia University http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00islamlinks/txt_jinnah_lahore_1940.html (Last Accessed 8th September 2017)

Additional Primary Sources

Curation of Governmental Source Material on Partition:

- British Library Online Archival Materials: http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelpregion/asia/india/indianindependence/indiapakistan/index.html

- National Archives: Selection of British Governmental Documents on the Lead-Up to Partition: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/the-road-to-partition/

Contrast the opinions of the ‘Great Men’ of partition with first-hand accounts and oral testimonies from those who experienced the results of Partition.

- For a remarkable collection of interviews conducted over decades by the journalist Andrew Whitehead as part of the ‘Partition Voices’ Oral History Project, see: http://www.andrewwhitehead.net/partition-voices.html

- ‘National Archives: Panjab 1947’: Contains the testimonies of individuals who experienced Partition in the Punjab region, now based in British. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/panjab1947/default.htm

Secondary Reading

For a thorough investigation of much of the recent scholarly literature on the Partition, see David Gilmartin, ‘The Historiography of India’s Partition: Between Civilization and Modernity’, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 74, No. 1 (2015), 23-41

For an excellent recent study by an Oxford historian, see Yasmin Khan, The Great Partition (Oxford, 2007)

Urvashi Butalia, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (Durham, 2000) - Pathbreaking work that uncovered the lived experience of Partition.

Figure 1: ‘An attempt to show the population transfers in August 1947; the pie chart applies to post-1947 India’

Author Details

Sean Phillips (DPhil candidate in History, Nuffield College)

Sean is interested in histories of empire and expansionism in a global context, histories of decolonisation and histories of the ‘Pacific World’.