Intellectual History

The Intellectual strand offers an interdisciplinary approach to Intellectual History, with chronological and global reach. Graduate students have the opportunity to study thinkers and ideas from the fourth to the twenty-first centuries, in diverse transnational geographical contexts. The course is designed to encourage students to work in and between areas such as Global Intellectual History, the History of Scholarship, the History of Science, the History of Art, Historiography and the History of Political Ideas, to name but a few. In the core course you will have the opportunity to experience and to combine a variety of approaches to Intellectual History in creative and innovative ways, and in doing so help to shape the future of this dynamic and exciting field.

Oxford is home to one of the largest communities of intellectual historians in the world, with expertise in every major area of Intellectual History. These scholars are supported by world-class libraries (the Bodleian, the major resource for intellectual historians), museums (the Ashmolean Museum and the Museum of the History of Science), centres, institutes and dedicated Intellectual History lecture series (the Berlin and Carlyle Lectures), and are engaged in exciting projects to create major digital resources in the field (Cultures of Knowledge).

Course Organisation

Alongside Theory and Methods, students spend their first term studying Sources and Historiography. Taught across eight seminars, you will be introduced to the philosophical background and methodological approaches to Intellectual History. You will study a combination of key thinkers (central figures might include, for example Michel Foucault, Arthur Lovejoy and Quentin Skinner) and new approaches to the discipline (for example, comparative, feminist and global intellectual history).

Meanwhile, in the Skills component of the course, you will be able to learn a language, such as Latin, French, German, Italian, Spanish and many more. You can take dedicated Languages for Historians classes, specifically targeted to the needs of History scholars. You will be able to learn palaeography so that you can read manuscript and archival source materials. We have some of the most advanced digital humanities resources in the country, and you will be able to acquire the technical skills you need. You can also work on manuscripts and books with the guidance of leading scholars.

In the second term, students take one of a wide portfolio of Option courses. Those particularly relevant to the intellectual history typically include:

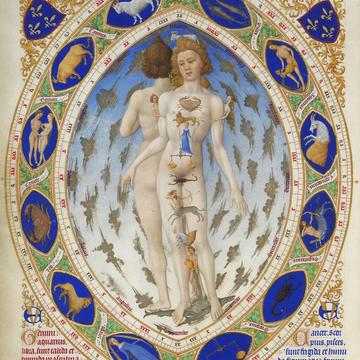

The Twelfth-Century Renaissance is an interdisciplinary paper in intellectual history designed to give students a broad overview of the content and applications of learning in the twelfth century. It therefore covers a wide range of different curricular subjects from the perspective both of their sources (the classical textual tradition of ninth-century learning; the impact of newly translated texts; the consequences of personal contact with Muslim and Jewish scholars in Sicily and the Iberian peninsula; the influence of empirical discovery) and of their application through cathedral schools and royal courts to society at large. The course comprises eight classes, organised around the seven liberal arts (the trivium and the quadrivium) and the three higher faculties of the medieval schools.

The ‘globalization’ of history has been the most visible and significant development in historical scholarship of the past decade or so. Historians are increasingly aware of the need to place their work in a context that spills over national, regional, or civilizational boundaries. Some of the most exciting work has emerged from probing the global dimensions of the ‘early modern period’ before the rise of European world domination. This course will introduce the two principal methodologies involved in doing this new large-scale history – the connective and the comparative – through a series of seminars led by one European historian and a different specialist in cultures outside of Europe each week. In pursuit of the connective we will consider what happened when Europeans began to traverse the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and became entangled in a newly diverse range of societies. For example, what kind of architecture resulted when Portuguese ecclesiastical styles were transplanted to the tropics? Other weeks will take a more comparative approach. Considering the way in which Chinese intellectuals turned to classical texts in formulating ‘Neo-Confucianism’, for example, should help us see the over-familiar European themes of Renaissance and Reformation in a new light.

How have people understood the self in the past? How have they conceptualized emotions? Is there a self before 1700? How do different cultures conceive of the self and how do they understand spirituality? What is the relation between the individual self and the collective? This course seeks to understand ways of approaching the self and psychology in different times and places. It also seeks to explore ways of incorporating subjectivity and emotions of people in the past in how we write history; and to question the sociological, collective categories of analysis that historians often employ. Each session will take a particular example of a cultural context and explore how historians could write the history of subjectivity. The sessions will draw on different types of source material – diaries, letters, visual sources, material objects, travel writing, memoirs, court records, micro-historical material, oral history – and consider the problems and possibilities they offer. Four of the sessions will be on the early modern period; four will be on the modern period; however, in their assessed essay, students may concentrate on either the early modern or the modern period. The course deliberately bridges the early modern and the modern because the historiography itself does. This enables productive comparisons.

Creating the Commonwealth looks at the intersection of religion and politics in the work of three of the most important early modern intellectuals: Hugo Grotius, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. The course begins with an examination of Grotius’s approach to the problems of religious and political division within Europe and the challenges brought by Dutch expansion in the New World. Grotius argued that political communities could be built upon principles which all human beings held in common, while allowing scope for different kinds of churches and religious groups. We will consider how he made this case, drawing upon classical, historical and religious arguments. Hobbes was a follower of the Grotian project, in that he recognised the foundational importance of natural law principles. But Hobbes was also critical of the thought that the Grotian scheme might be sustainable without a radical reconstruction of the natural law ideas that Grotius had proposed, and in the seminars on Hobbes we examine the character of his controversial response in De cive and Leviathan. Turning finally to Locke, we examine a thinker dealing with the legacy of the ideas of Grotius and Hobbes, and examine the ways that he sought to mediate their influence in the political theory of the Two Treatises of Government and his powerful work on religious toleration. Studying these three thinkers together reveals the dialogical features of some of the most important texts in the western intellectual tradition, and casts new light upon some of the ideas regarded as foundational to modern political thinking.

This option offers the opportunity to engage with a range of exciting new scholarship on the Enlightenment, covering the period from the second half of the seventeenth century to the end of the eighteenth century. It takes inspiration from recent rebuttals of the postmodern critique of the ‘Enlightenment project’, and addresses the subject in comparative and transnational perspective. We shall cover Enlightenment both as an intellectual movement and as a social phenomenon, examining how thinkers across Europe engaged with new publics. For the first four weeks we shall explore the major interpretative issues now facing Enlightenment historians, including:

- the coherence of Enlightenment – whether we should think in terms of one Enlightenment or several;

- the importance and duration of ‘radical’, irreligious Enlightenment;

- the relation between Enlightenment, the republic of letters, and the ‘public sphere’;

- the politics of Enlightenment: public opinion, reform, and revolution.

During the second half of the course, participants will be encouraged to set their own more precise study agenda, related to the topics of their course papers. They may explore in more detail the intellectual content of Enlightenment, its various contexts, its social framework, and its impact, within and across national and political frontiers. Topics which might be studied at this stage are:

- Enlightenment contributions to natural philosophy, and the ‘arts and sciences’;

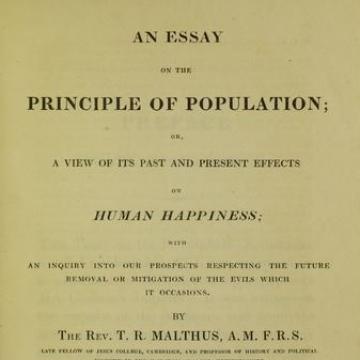

- the Enlightenment ‘science of man’, as pursued in philosophy and political economy;

- writing sacred, civil and natural history in the Enlightenment;

- women, gender and Enlightenment.

Participants will also be encouraged to attend the research-oriented Enlightenment Workshop, which meets weekly in Hilary Term.

Faculty and Research Culture

The Faculty and University have particular strengths in Global Intellectual History, Historiography, the History of Art and Culture, the History of Political Thought, the History of Religion, the History of Scholarship and the History of Science. We have a very lively research culture, with seminars involving leading international scholars just about every day of the week. The History Faculty is home to the major international project Cultures of Knowledge: Networking the Republic of Letters 1550-1750, and has close links with the Voltaire Foundation.

Faculty postholders working in relevant fields include:

See all their websites for more details of their research interests, and for the full range of topics on which they would be interested in supervising graduate students, only partially captured by the brief descriptions above.

Faculty seminars bring together staff, doctoral and master’s students working in the field, to hear speakers including doctoral students, external and internal to the university.

Seminars relating to this strand include:

- The Early Modern Intellectual History Seminar

- The Enlightenment Workshop

- The Historiography Seminar

- The History of Pre-Modern Science Seminar

- History of Science, Medicine and Technology Seminar

- History of the Exact Sciences Seminar

- The Oxford Political Thought Seminar

- The Relation of Literature and Learning to Social Hierarchy in Early Modern Europe